Crediting in type design

Crediting in type design acknowledges the collaborators whose contributions shape the fonts we use daily. This is our proposal to foster transparency and respect within the design community.

Type design is a problematic field when it comes to crediting for several reasons. It can be done by a single person working from a home office, or by large teams of professionals, each of them dealing with very specific parts of the development and release cycle. Many of the necessary tasks may require in-depth research, hiring external consultants, or outsourcing processes. These external collaborators may not push nodes around, but they do contribute toward the final product’s quality — or lack thereof.

Another important fact that is obvious but should be mentioned is that type design has changed together with technology — from a craft to an industrial trade to a technical design field. As part of an article about intellectual property and copyrights, Charles Bigelow compares type design to a monumental sculpture or to the design of a programming language. Bigelow helps us understand some of the first things we need to consider when discussing credits. In short, type design has a strong artistic component — parts of the process imply creativity — and it has become a technically challenging trade — other processes require specific technical knowledge.

At the same time, the artistic qualities of a typeface are not solely related to the drawing of lettershapes. In creative terms, what we call the authorship of a typeface is much more than drawing outlines. The idea and concept culminating in the final shapes and how they work together needs to be credited as crucial artistic contribution. It is about the creation of something that is different, that is unique. As such, in some cases the technical side should also be acknowledged as part of the design. For example, Twin by LettError is a type family that changes according to data input; in this case the weather.

But where do you draw the line? As Bianca Berning points out, “For example VAR fonts are very technical,” acknowledging the designer is not done when the drawing is finished. “Engineering is a lot of work.” Unfortunately the current legislation about IP protection in our field is inconsistent and does not offer a useful framework. Some countries protect the design of letterforms, others treat typefaces as software code. Apart from the inherent moral rights, the conditions of intellectual property and conceptual creation most likely will have to be defined on a case-by-case basis. The goal of this article is to discuss a sound crediting strategy for typeface development which is broader and separate — even if related — from the definition of what authorship is in the type business.

The problem of giving appropriate acknowledgement is nothing new; history is full of erroneously credited work. For example there is the case of Miklós Kis, a Transylvanian Protestant priest and schoolteacher who grew deeply interested in printing after being sent to Amsterdam to help print a Hungarian protestant translation of the Bible. Kis became an accomplished punchcutter working on commission for printers and governments. As he returned to Transylvania around 1689, it is assumed that he left his matrices in Leipzig, which were then wrongly attributed to Janson based on a specimen sheet released by Leipzig’s Ehrhardt foundry around 1720.

Another case is about Philippe Grandjean, the punchcutter of the famous Romain du Roi typeface. The committee in charge met regularly with Grandjean to check on the status of his work, demanding many changes and adjustments, sometimes even requiring Grandjean to destroy his punches and matrices and start over completely. Interestingly though, Philippe Grandjean did not follow the committee’s drawings slavishly and, by doing so, his subtle interpretation resulted in a softer and more beautiful typeface.

And of course there are the many, many women executing their chores of making type in metal and phototypesetting that tended not to get much recognition or respect. Their contribution, especially in the drawing room where they turned the designer’s sketches into a functional type product, was crucial for the foundry’s success.

Why crediting is important?

In general terms, crediting influences the viewer and their judgement of the presented work. However, without a clear and concise standard defining different contributions from different parties, crediting becomes difficult and vague.

Crediting helps to create an appropriate labour hierarchy. It is not sufficient to only acknowledge the main player and therefore attribute genius to that one individual, especially when a team and distinct hierarchies are involved. This is especially true in multiscript type design, where collaboration is key and the technical contribution is as valuable as the design portion in order to complete a functional product. In addition, credibility and quality increase when the audience knows that knowledgeable professionals of the particular script took a formative role. Users are more likely to accept and favour designs with these attributes in place.

A crediting standard could also institutionalise a shared vocabulary of job titles and therefore improve the general understanding of the implied responsibility and involvement in the type design process. However, not always do job titles associate the level of authorship correctly, reflecting the actual engagement of all parties. The created context, thowould clarify responsibilities and hence accountability.

Nowadays freelancing is increasingly more common than fixed employment in type design. Consequently, professional careers depend on being affiliated with accomplished work. Crediting recognises their contribution and acknowledges the process as a team effort. The perceived value of type-making is thus raised within the field and in the eyes of the general public by crediting those associated with type design.

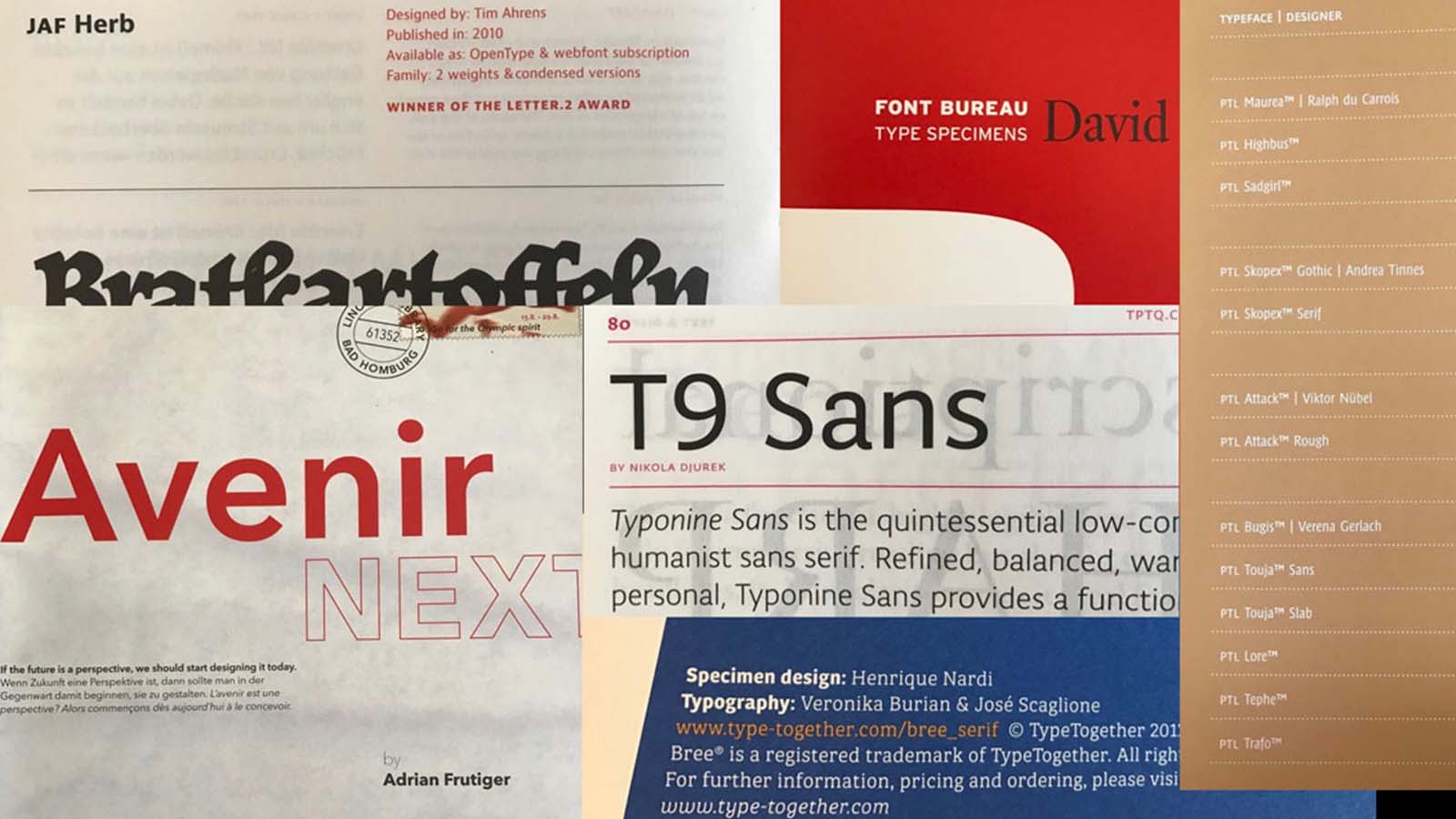

How is crediting currently done?

Surprisingly, there is no obvious difference between big and small players in how they deal with accreditation. The four most common ways are to credit either 1) only the studio/company, 2) only the name of the main designer, 3) inconsistently across media, or 4) as part of the general description. Other disciplines (e.g. printer, photographer, illustrator) are more often outlined rather than parts of the type design process.

The first obvious place to look for clues is in the graphic design field, given its professional proximity to type design. However, AIGA’s standards of professional practice lacks much clarity in their advice about authorship. It simply reads, “When not the sole author of a design, it is incumbent upon a professional designer to clearly identify his or her specific responsibilities or involvement with the design.”

Surprisingly, there is no obvious difference between big and small players in how they deal with accreditation. The four most common ways are to credit either 1) only the studio/company, 2) only the name of the main designer, 3) inconsistently across media, or 4) as part of the general description. Other disciplines (e.g. printer, photographer, illustrator) are more often outlined rather than parts of the type design process.

The first obvious place to look for clues is in the graphic design field, given its professional proximity to type design. However, AIGA’s standards of professional practice lacks much clarity in their advice about authorship. It simply reads, “When not the sole author of a design, it is incumbent upon a professional designer to clearly identify his or her specific responsibilities or involvement with the design.”

Another well established area that deals with accreditation are academic journals and papers. Here a variety of authorship conventions across disciplines exist. Some favour alphabetic order, others seniority, and some have specific rules that determine who is responsible for data collection, scientific research, or project direction. Probably the most widely used authorship rules are known as the “Vancouver rules” and were laid down by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

Their criteria for being listed as author read as follows:

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work;

- Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content;

- Final approval of the version to be published;

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Contributors who meet fewer than all four of the above criteria are not listed as authors. They should only be acknowledged.

The film industry can probably provide more useful tips since it shares some common traits. A film project involves an array of different roles: writers, editors, producers, directors, and actors, often grouped into guilds that advocate for their member’s rights, such as correct attribution of work. For example the Directors Guild of America permits a film to list only one director.

According to Robert Glatzer’s Movie Credits 101, “Credits aren’t really there for the audience. They’re there so the industry will know who did what on the film. They help with future jobs, with better contracts, with more deals and obviously with getting more money next time.” The point of view that detailed credits are for the industry rather than the users can be transferred into the type industry. Crediting the work, especially the technical roles in type design, is not necessary for selling fonts, but helps the development of the industry and the professional growth of people working in it.

On the other hand, the responsibility for selling the film to the wider audience lie with the opening credits or a title sequence that identifies only the major actors and crew. Here the order in which credits are billed generally signify their importance or are assigned in accordance to contractual terms. The same criteria is followed in printed advertising such as posters. The lead actors, director, or producer are spelled out in large letters since they represent a marketing argument for selling the product. If space allows, the extended credits go into the so-called billing block — often, and sadly, very small and illegibly on posters. This information usually consists of secondary companies, actors, directors, producers, and crew members.

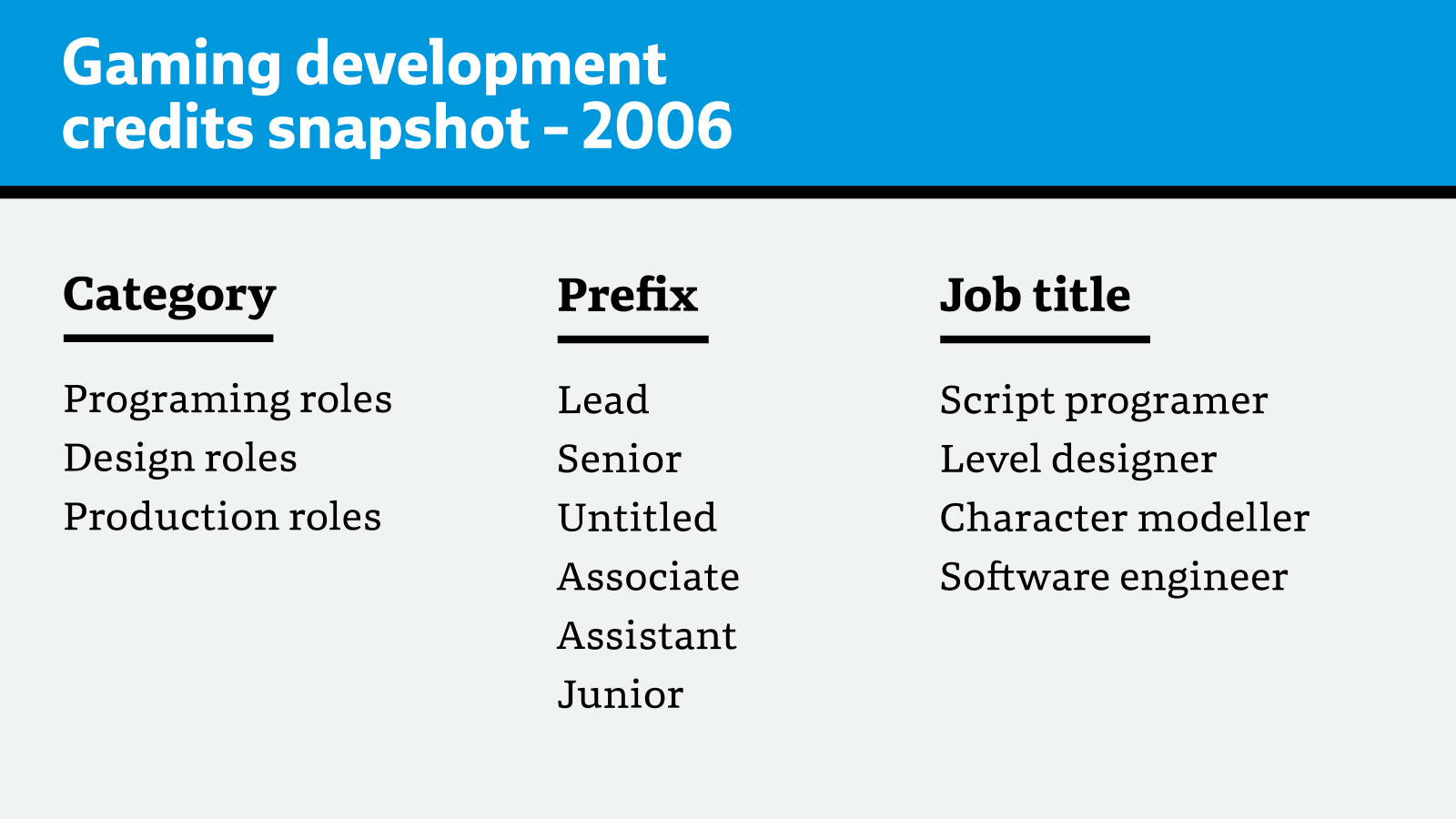

The last industry that could grant some pointers is in gaming because, though 100 or 1000 times larger than typography, they face similar issues. The International Game Developers Association formed a volunteer-based commission that produced two documents. The first one was published in 2006 and is simply a snapshot of how attribution was done at the time. One of the interesting yet understandable findings is that they recognized two facts:

1) Crediting was very informal in terms of finding out who did what. “This can be as informal as passing around a sheet of paper where the employee is expected to write down whether he worked on a game and what role they provided, or an oligarchic process where the top managers of a project sit together and try to remember who all touched the game and what their capacity was.”

2) The most used systems were based on tiers and categories.

Eight years later the committee published an updated document that provided very specific rules about crediting. It spelled out four important factors:

- Inclusion: who gets credit

- Attribution: what credit people get

- Usage: how they get credit

- Methodology: procedures for collecting credits

In this document IGSA also provides for a disambiguation system based on prefixes used next to job titles. This allows for professionals to receive appropriate attribution based on seniority or responsibility level, such as having a lead designer and a junior designer.

Based on the findings above, a set of criteria and a usable crediting system can be developed. It should be flexible enough to fit big companies as well as one-person operations. It needs to be equitable to give credit according to the amount and importance of one’s work. A threshold should be set for the nature and amount of work during the development process that deserves recognition. The system needs to be forward-looking to fit possible changes within the industry and all related occupations. It should be commercially viable to allow for successful sales efforts, e.g. by naming main designer. And finally, the system should be legally reliable in order to avoid legal action and controversy as much as possible.

As our former teacher and good friend Gerry Leonidas puts it, “A standard approach across all projects in a company is possible and can be a differentiator for a foundry that does it properly.”

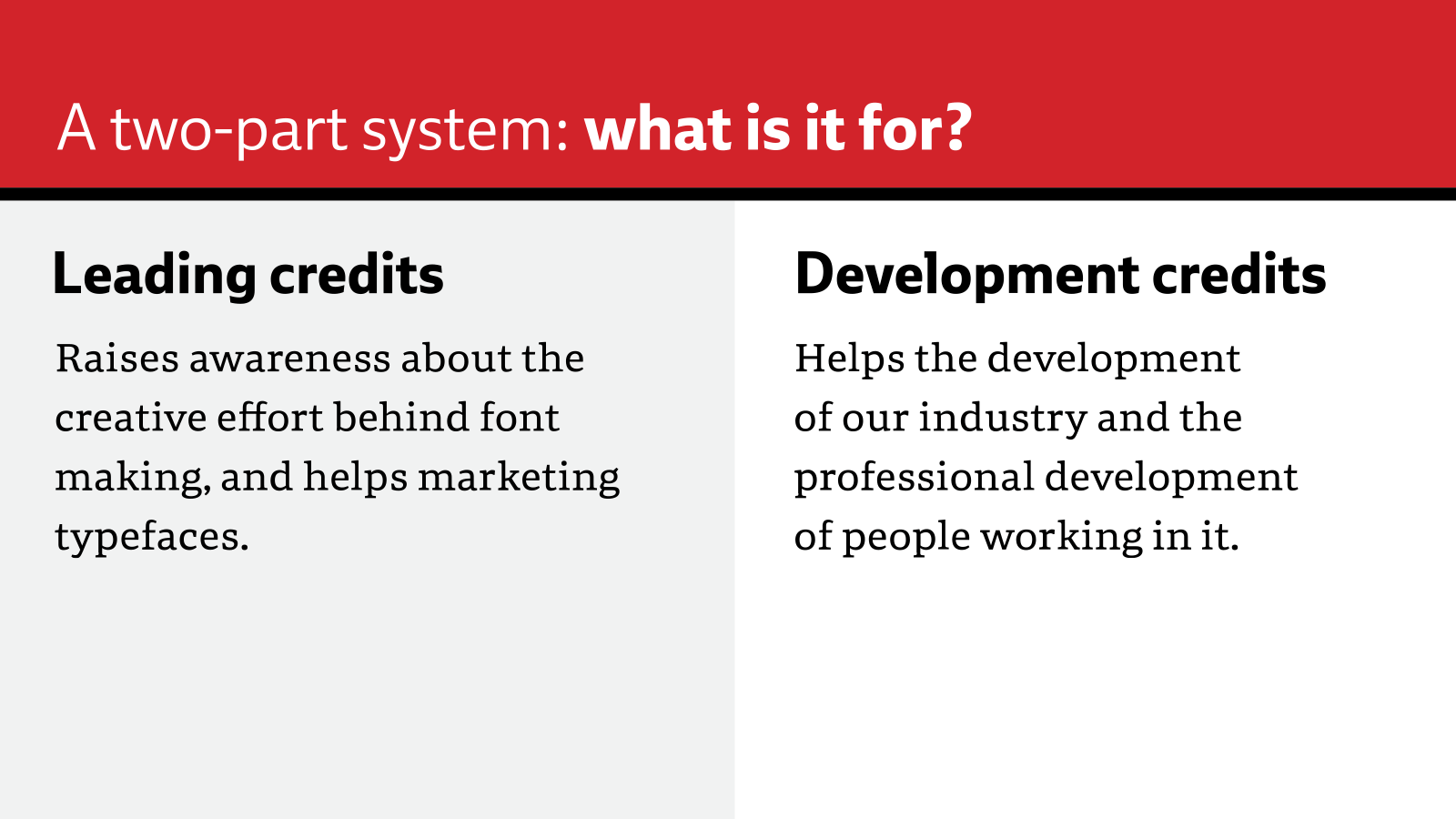

Two-part system

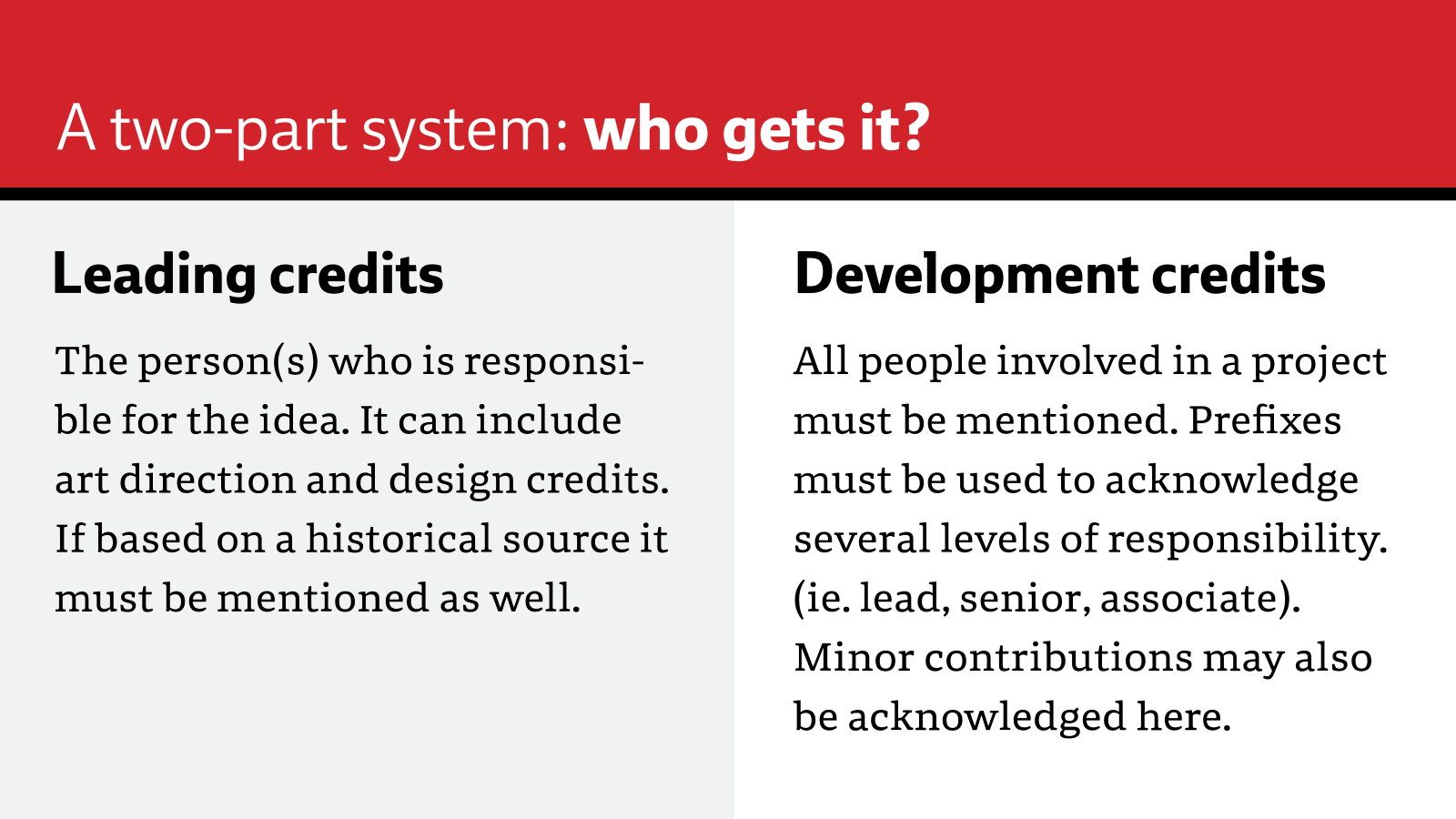

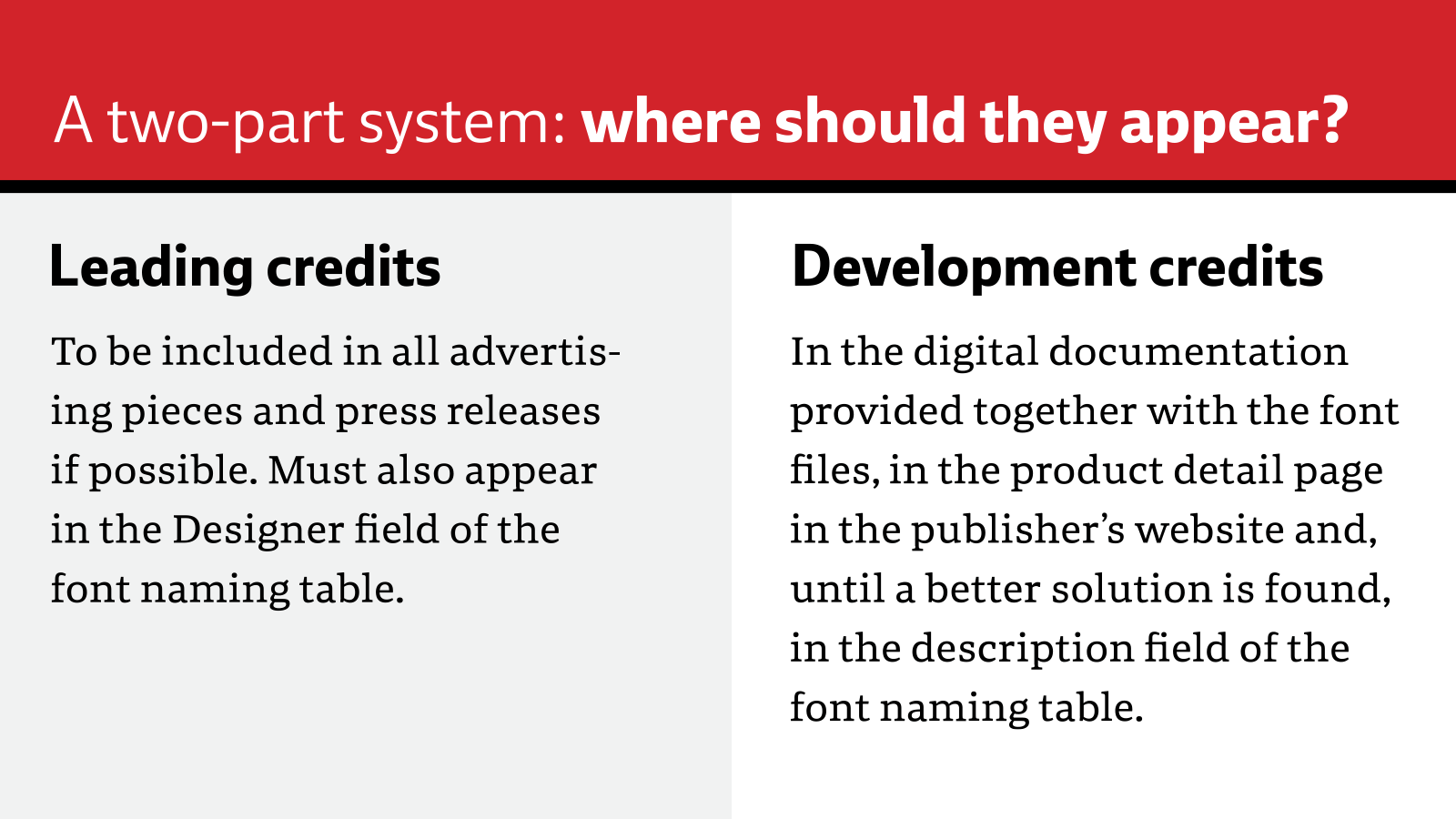

Inspired by the film and gaming industries, a two-part system offers a potential solution for the world of typography. Credits would be divided into ‘Leading’ and ‘Development’, which are then divided further into subcategories and titles. A singular Leading Credit would mainly include authorship attribution: crediting the underlying idea and concept of the typeface, which suggests a strong visionary and artistic component for the entire project. Depending on the size of the project and people involved, design can be split into concept, art direction, lead design, and historical source. In the case of multiscript commissions, this categorisation can then be repeated for each script.

Optionally, the name of the publisher could be added after the design credit in those cases where it may represent a commercial advantage. For example, when the publisher’s name guarantees a certain level of quality, or when the publisher’s website is the primary sales channel.

The authors and any other roles would be combined under Development Credits, from design, engineering, and quality assurance to consultancy, marketing, external services, publishing, and more. Each of these sections could then define specific tasks and level of titles. For example, it could look like this:

Engineering > Lead/Senior/Untitled/Assistant >programer/hinter/kerner/….

Resulting in the title Engineering: Senior programmer.

Inspired by the film and gaming industries, a two-part system offers a potential solution for the world of typography. Credits would be divided into ‘Leading’ and ‘Development’, which are then divided further into subcategories and titles. A singular Leading Credit would mainly include authorship attribution: crediting the underlying idea and concept of the typeface, which suggests a strong visionary and artistic component for the entire project. Depending on the size of the project and people involved, design can be split into concept, art direction, lead design, and historical source. In the case of multiscript commissions, this categorisation can then be repeated for each script.

Optionally, the name of the publisher could be added after the design credit in those cases where it may represent a commercial advantage. For example, when the publisher’s name guarantees a certain level of quality, or when the publisher’s website is the primary sales channel.

The authors and any other roles would be combined under Development Credits, from design, engineering, and quality assurance to consultancy, marketing, external services, publishing, and more. Each of these sections could then define specific tasks and level of titles. For example, it could look like this:

Engineering > Lead/Senior/Untitled/Assistant >programer/hinter/kerner/….

Resulting in the title Engineering: Senior programmer.

The list is flexible and can be reduced or expanded in accordance with the requirements and particularities of each project. Team members who make a substantial contribution to the project in any of the categories should be credited and persons with less engagement can be acknowledged with a text like, “Special thanks to” or “With the collaboration of”.

All public-facing credits should follow this two-part system. The Leading Credits must be included in all promotional materials as much as possible and the lead designer should be clearly indicated within the font naming table. On the other hand, the Development Credits should appear in all digital documentation provided with the font file, such as a digital specimen. The product detail web page and a special section in the typeface’s OpenType table should also feature the full list of people and their job titles involved.

Fair and proper crediting is important for the typography industry as a whole. It nourishes the community and helps to establish type-making as an endeavour worthy of people’s attention and appreciation.

This article is based on a talk held at ATypI 2017 and written by Veronika Burian and José Scaglione with proofreading by Joshua Farmer.